The name of Bedlam drums up difficult reminders of discrimination, ignorance and the insensitivity of historical attitudes to mental heath. But we don't think very much of the women who found themselves within the establishment's stone walls.

,_St._George's_Fields,_Lambe_Wellcome_V0013731.jpg) |

| Wellcome Collection, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons |

Bedlam (or 'Bethlem', as it was originally called) was established as a religious house in London in 1246, to house men and women devoted to worship, by Simon Fitz-Mary, Sheriff of London. In 1330 it was first referred to as a hospital but its associations with mental heath began in 1402. Stow, the Tudor traveller and writer, wrote that 'some time a king of England, not liking distraught and lunatic people to remain so near his palace, caused them to be removed farther off to Bethlem'. Stow doesn't state the individual king involved, but if it was indeed in the very early fifteenth century this would place it during the reign of Richard II or Henry IV.

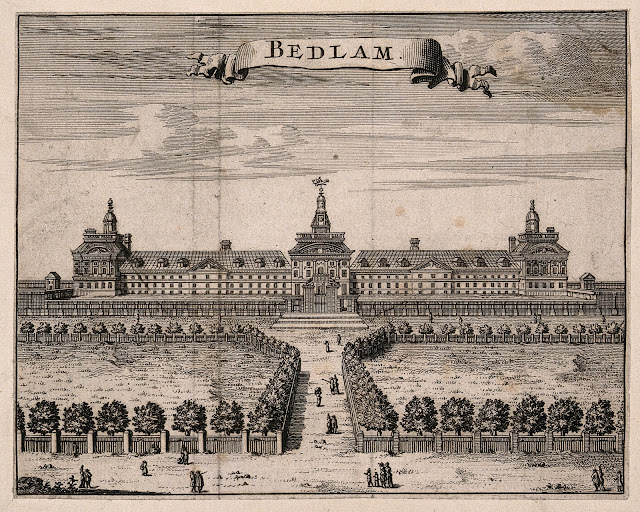

By the later seventeenth century the hospital was rebuilt, the Victorian historian Timbs stating it was 540 feet long and 40 feet wide with gardens surrounding it, in which the patients were allowed to walk. Patients would have looked up at the high stone walls and the secure gates, along with the somewhat insensitively placed sculptures of 'Raving and Melancholy Madness' flanking the entrance. Men and women were housed in separate areas, and there were bathing facilities where hot or cold baths could be given. In 1754 Bedlam housed 150 patients. In 1849, there were 344 patients, 194 of them women.

One women at Bedlam not long after renovation works had been carried out to the building in the eighteenth century was Hannah Snell. Born in 1723, in her early twenties Hannah had dressed as a man and fought in battle, sailing to India and participating at the Siege of Pondicherry, no one suspecting during the warfare that she was really a woman. She revealed her identity in 1750, and received a great deal of attention as well as curiosity about her adventures. After raising a family, in 1791 at around the age of 68, she was admitted to Bedlam, possibly in relation to a declining mental health condition such as dementia, which would have been poorly understood at the end of the eighteenth century. She died, in the hospital, soon afterwards, on 8 February 1792.

Timbs, who was writing in 1855, praised Bedlam's 'improved management' that had been introduced in 1816, and painted a picture of contentment at the hospital as he wrote that 'patients employ themselves in knitting and tailoring, in laundry-work, at the needle, and at embroidery; the women have pianos, and occasionally dance in the evening'. Men, he said, played cricket, billiards and read newspapers and periodicals. He refers to the idea that keeping busy 'often induces speedy cure', a sentiment very different to today's treatments, which include talking therapies and analysis of problems through counselling to improve mental health. He also added that not everyone was shackled or restrained, although before 1814 he said 'the rooms resembled dog kennels; the female patients were chained by one arm or leg to the wall'. They walked barefoot and slept on straw. Judging from Timbs' words, this may indeed have been the treatment received by Hannah Snell, although the practice of admitting members of the public to gawp at the patients for a fee was abolished, he claims, in 1770.

One woman patient, who Timbs does not name, was chained to her bed for eight years. He described her as so dangerous that staff at the hospital feared that she would murder them if she managed to free herself. He adds that when released, she became 'tranquil' and was given two dolls to look after, which she did as if they were her own children.

Margaret Nicholson was also admitted to Bedlam for her assassination attempt on George III. She entered the hospital's gates in 1806 and died there in 1828. She would have been housed at the same time as James Hadfield, who had also tried to shoot George III at the Drury Lane Theatre in 1802. He was admitted in that year and died inside Bedlam's walls in 1841.

Liked this? You might also like Vulcana, The Victorian Wonder Woman, The Queen of Beauty: Jane Georgiana Seymour and Duchesses of Belvoir Castle - a Guest Post by the Duchess of Rutland.

Like women's history? I explore some stories of forgotten Medieval women in my book Forgotten Women of the Wars of the Roses, published by Pen and Sword. It examines the lives of women collectively as well as individuals, during the Wars of the Roses conflict in the fifteenth century. Order your copy here.

Never want to miss a post? Subscribe to my newsletter here:

Sources:

Timbs, The Curiosities of London (Bogue, London 1855)

http://www.hannahsnell.com (accessed 22 March 2023)

0 Comments